Multicultural teams and active listening

Authentic active listening is the foundation of effective communication. It encourages focus on the speaker’s content, emotions, and body language. Empathy, authenticity, and respect for the speaker are values that we can draw from Japanese culture. In the spirit of active listening, the Japanese tend to avoid evaluating the speaker’s words or interrupting them with suggestions. How can we benefit from applying these values to multicultural Scrum Teams?

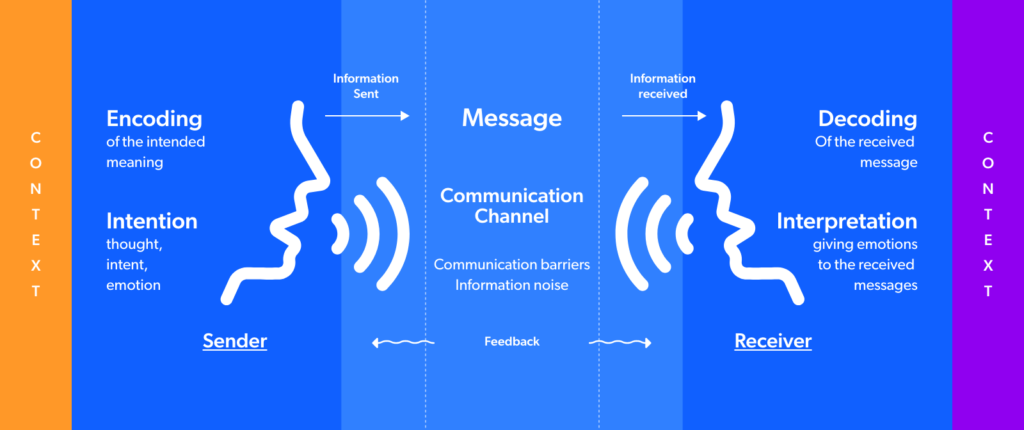

There is no doubt that people coming from different cultures, as is the case in software development teams, see, interpret and evaluate differently. Consequently, they make different choices. In the case of multilingual Scrum Teams, the process of coding and decoding symbols and messages is tied to each individual team member’s background.

Consequently, the effort to actively listen in multilingual teams is much greater than in monolingual ones. On the team level and in the relationship with Stakeholders alike, there are also many “variables” that can disrupt the process. This, of course, has an impact on the delivered product or solution. If we take into account Lasswell’s model, it becomes clear that the communication process itself is complex, even in just one language and culture:

If cultural differences, different languages, emotions, haste, fatigue, varying levels of product knowledge, and software development difficulties are added to this model, teaching active listening techniques can serve to solve problems more effectively. It will also reduce stress and lead to the more regular delivery of functionalities.

How does one build a common language?

For the purposes of this article, let’s assume that our Scrum Team has Polish Developers and Scrum Master. The Product Owner and Stakeholders are German, and the product is developed for that market. The business language, the lingua franca, is English. In this complex case, for any interaction to take place at all it is the individual team members who must have at least two specialized languages and two specialized cultures (Polish-English and German-English). On top of that, they must be able to connect between the languages and cultures in the specific context of a single Sprint. To do this, they use business language, a specific variant of English, in the use of which the emphasis is on the content rather than the form of the language. So, anyone who fears that their language competence is not sufficient should understand that IT is all about the specific use of language for common communication. It’s little use graduating in English with honors and mastering the intricacies of grammar and syntax. Instead, you will have to learn an idiosyncratic, specialized language “co-created” by the individual team members: Frank, Bjorn, or Oskar.

Lingua franca – Frank’s lingua?

Business English, a lingua franca, is a relatively autonomous linguistic creation in which there is a transfer of relevant grammatical, semantic, syntactic, and pragmatic structures from the national language. If we stay with our example, Polish for Scrum Master and Developers and German for Product Owner and Stakeholders. Therefore, the languages produced by team members are either similar or different. The closer the languages are on the genealogical tree of languages, the less noticeable this difference should be. To this conglomerate of specialized languages, dense as the tasks piled up in the backlog, one should add certain abbreviations, terms, phrases, vocabulary, and terminology related to software development and management specific only to the IT industry and the given company. So what “language creation” the team will ultimately use depends on the type of work the team is doing and the company model.

Any junior or new specialist in a particular field, wishing to become a member of such a team, will have to fit into the convention chosen by the company and the team within formal and less formal communication structures. Only then will they be able to co-create a “community of practice” and, so to speak, a “common repertoire,” which is really a mini-specialist language and a kind of specialist culture.

Getting to know the “common repertoire” may give rise to all sorts of distortions at the level of understanding the sender’s intentions or needs. Other times there will be problems with the messages – they will be too long or badly worded, or, for example, manipulated by the perceptual filter of the recipient. Things won’t be made easier by communication noises in the “communication channel”, nor at the level of specialized language: unclear pronunciation, mispronunciation, superimposition of the native language on the lingua franca, mishandling of terminology, technical language, or use of linguistic calques. If we add the stress caused by the fear of correct interaction and emotions, the obstacles to understanding the correct message start to mount.

Hear what is being said – it pays off

The ultimate goal of active listening is to foster positive team change by creating communication bridges. Proper understanding of each other by members of multicultural teams is crucial for the product or functionality delivered.

As Kubota, Mishima, and Nogata’s [2004] study also shows, managers who learned active listening were much better at supporting employees. They also created a much more safe and more empathetic environment for sharing the challenges of work. That’s because when a listener takes care of the speaking space by reducing or eliminating questions, it leaves room for silence. Silence, in turn, gives space to process what has been said; to work through one’s thoughts, and figure out what solution to choose in a given case. An active listener must also have good intentions, and be “tuned in” like a decoder to the information being conveyed, as well as to the way it is given. All non-verbal cues enter into this process: tone of voice, facial expressions, body, and speed of speech. These can often be incompatible with the message being transmitted. The listener’s body language is also essential. In the age of video conferencing, this is particularly salient. If the listener has the camera on during the meeting, maintains eye contact with the speaker, has appropriate facial expressions, and shows attention, only then can we talk about attentiveness. This is the first step to the formation of understanding and, over time, trust that builds sincere and open communication.

In summary, why not teach active listening techniques in Scrum Teams? After all, in a complex work environment, they contribute to supporting Scrum’s core values. Moreover, as Bauer and Figi’s [2008] in-depth study of active listening among IT professionals indicates, these techniques also have positive implications for other forms of communication, such as more effective instant messaging.

References:

1. Rogers, C. R., & Farson, R. E. (1987). Active listening. In R. G. Newman, M. A. Danziger, & M. Cohen (Eds.), Communicating in business today. DC Heath & Company.

2. Bauer, C., & Figl, K. (2008). ‘Active listening’ in written online communication-a case study in a course on ‘soft skills’ for computer scientists. In 2008 38th Annual Frontiers in Education Conference (pp. F2C–1). IEEE.

3. Kubota, S., Mishima, N., & Nagata, S. (2004). A study of the effects of active listening on listening attitudes of middle managers. Journal of Occupational Health, 46(1), 60–67.

4. Zając J., ‘Specyficzna komunikacja multikulturowa i multilingwalna w korporacjach globalnych’, Wydawnictwo Naukowe UW, 2013

5. O’ Bryan A., ‘How to Practice Active Listening: 16 Examples & Techniques’, 2022.

Katarzyna Młynarczyk